3rd Bomb Group Photos

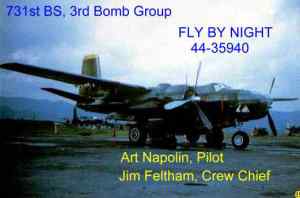

731st BS — Fly by Night

731st BS — INVOLUNTARY

by Chester L Blunk, Lt. Col. USAF (Ret)

and Andrew G. Anderson, Capt. USAFRes. (Ret)

By Andy Anderson

We had departed George Air Force Base early that morning, in a C-47 “Gooney Bird”, to fly to Hill and pick up B-26’s the 47th bomb Wing had flown after World War II, developing Night Intruder tactics.

We were now ferrying them to George where we were to undergo six weeks of intensive training for our role in the Korean “Police Action”. Our squadron was one of four in the 452nd bomb Wing, a reserve organization headquartered at Long Beach airport. We had been called into active duty less than two weeks before. Historically, we were the first Air Force Reserve unit to ever be called to active duty intact.

The 728th, 729th, and 730th squadrons were designated to fly daylight operations, but the 731st had been tapped to be attached to the 3rd bomb Group, a B-26 group that had come up the Pacific island chain in World War II and wound up on occupation duty at Yokota Air Base outside Tokyo. It had only two active squadrons, the 8th and 13th Bomb Squadrons, famous old-line outfits that could chase their pedigrees to pre-World War I. This would balance the effort between day and night operations.

With permission to take off, I advanced the power on the two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engines, and listened to the ascending roar of a pair of the sweetest reciprocating engines ever made. Satisfied, I released the brakes and started the takeoff roll. As the airspeed passed 110 MPH (that’s right, 100 MPH – these were OLD War Birds), I applied back pressure on the yoke to start my rotation. As the nosewheel left the ground I heard an exclamation from the crew chief. I glanced at him to see what was up. He was pointing at the gear indicators. I thought he was trying to remind me to retract the gear. I called “Gear up” and he pointed at the gear indicators again. A closer look showed all three gears indicating the “up” position, but he had not moved the gear handle to the up position. Because the aircraft was light, it had rotated immediately with my back pressure on the yoke, and was airborne before the gear started to retract.

I called Hill tower and asked for permission to remain in the local area, and more out of curiosity than anything else, I asked the crew chief to put the gear handle in the “up” position. The gear immediately began to extend and lock down. Several cycles on the gear handle left no doubt that something was wrong, and we had better return to Hill to find out what. We notified the tower, and returned to land. It takes a lot of trust to land an airplane with the gear indicating opposite what it should be with respect to the operating handle position. We went through the routine the of tower fly-by while “every busybody” on the base took a look through binoculars. After two requests to fly a little close, I aimed dead at the tower and went over it with little room to spare. That finished that, and I was cleared to land. Luckily , it was an uneventful landing. At the end of the runway the crew chief went out the nose hatch and placed the gear safety pins in their positions, and we taxied to the ramp.

An hour or so later it was determined that “somebody” had reversed hydraulic lines on some module in the gear system. With the gear lever once more in the “down” position, we taxied out and took off. The gear remained extended until I called for “gear up”, and the handle was moved. The gear did its thing right. Problem solved.

An hour later, on autopilot, we were finally in a relaxed posture. We both became aware of the odor no one likes to smell in an airplane; the odor of burning electrical insulation. A quick scan of the instrument panel showed no wisps of smoke. The instruments were reading normally, but the odor was still in evidence and getting stronger. Then the crew chief discovered that some hydraulic fluid had evidently leaked into an electrical junction box that serviced the heated-suit outlet, and had shorted it out. He quickly located th circuit breaker and pulled it. The smoke and odor immediately diminished. We didn’t feel it was necessary to declare an emergency, and pressed on for George AFB.

Somewhere south of Las Vegas th crew chief made the remark that the airplane was acting just like an “Involuntary Recallee,” which we all were.

There was a fine distinction in personnel called to active duty. If you asked for recall, and they granted it, you were called in on an indefinite basis, but if they ordered you to active duty, they had to make it for a specific term, thus the “Involuntary.” In the case of the 452nd, that length of time was 21 months. You could, at a later date, ask for an indefinite extension, but if you did not, you could not be kept longer.

I am not sure who had the idea; who did the job; or when it was done, but old “958” had a bright yellow, on word addition painted diagonally on both sides of the forward fuselage.

Thus you have the name for this book. We all were in the same boat, and our record was just as good for the men of the 731st as the two aircraft I have just

731st BS — MISS FITT

731st BS — 44-35989

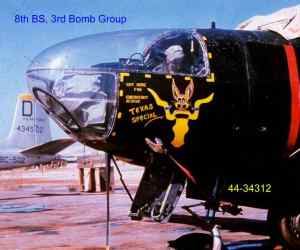

8th BS — Texas Special

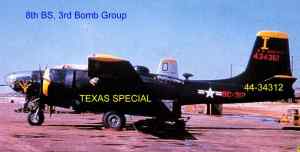

8th BS — Texas Special

8th BS — Midnight Rendezvous

8th BS — 44-35402

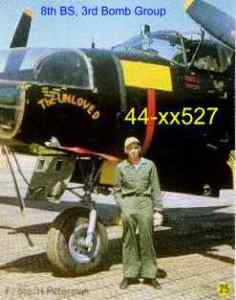

8th BS — Unloved

8th BS — Deborah’s Dad

8th BS — 44-35736

13th BS — Empty Saddle

13th BS — Empty Saddle

13th BS — DOT

13th BS — Mc

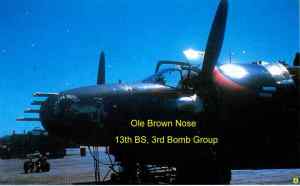

13th BS — Ole Brown Nose

13th BS — 44-35595

13th BS — 44-35821

Yellow Peril 966

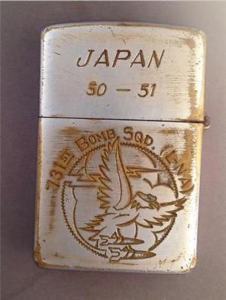

Zippo Lighter 731st Bomb Squadron